History of radium research in Austria

Like most of the webpage, this was a side-project during a pandemic lockdown in Vienna.I am a researcher at IQOQI Vienna, which is based at the former Institute for Radium Research (Radiuminstitut). Our buidling has a long and exciting history. The institute was built in 1908 by the then imperial academy. At the time, there was a strong scientific and economic interest and excitement to conduct research on radioactivity. Two decades earlier, Marie Skłodowska Curie had isolated radium from pitchblende, a mineral known from the 16th century on or earlier, when silver mining started in the Ore Mountains at Joachimsthal/Jáchymov (Bohemia). Early mining had no use for the strange mineral. It was relatively heavy, otherwise a good indication for a valuable ore, but no metal could be extracted by the early mining technologies. At the dumps, it weathered down, oxidized and developed bright colours. By the 19th century, it was understood that these oxides are compounds of uranium that could be used to manufacture coloured glasses. A prosperous glass manufacturing industry developed around Joachimsthal/Jáchymov, then part of a monarchy, whose capital was Vienna, where the institute was built to catch up with the research of the Curies in France.

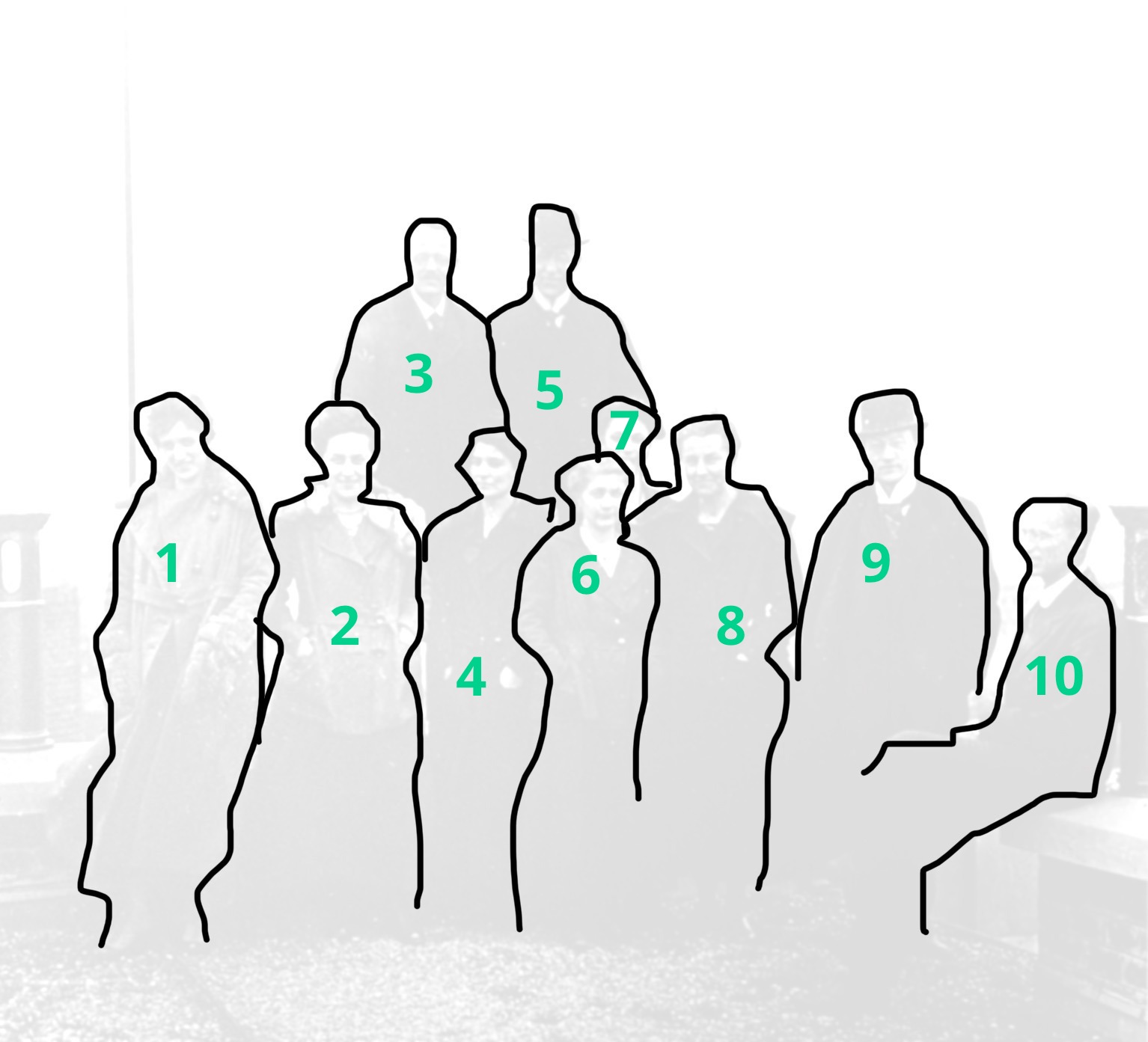

- Eleonore Albrecht

- Anna Gabler

- Ludwig Flamm

- Friederike Friedmann

- Victor Hess

- Grete Richter

- Maria Szeparowicz

- Hilda Fonovits

- Erwin Schrödinger

- Hans Thirring

I first saw it as a reproduction at the kitchen and common room of IQOQI-Vienna. I found it absolutely stunning and mysterious. When was it taken? Why was the picture taken? Schrödinger is clearly there on the right under his hat, but who are the others? What was their role at the institute? What research did they do?

Some of the answers can be found in the dissertation of Maria Rentetzi, Trafficking Materials and Gendered Experimental Practices: Radium Research in Early 20th Century Vienna, and references therein. Further resources are listed at the end of this page. In what follows, I will give a brief summary stripped down to the most basic information.

When was the picture made? According to Rentetzi (2009), the picture was taken "shortly after the first world war." A very similar photograph can be found in Bischof (1989), where it is said that the picture was taken in 1919, but no further details are given. The picture from Bischof (1989) has a very bad quality, but there is the same angle, a similar arrangement of people wearing the same or similar clothing. Given all this, it seems reasonable to me that the picture was taken roughly between mid November 1918 and the first half of 1919. I could not get a more precise date.

- The third person in the first row from the left is Friederike Friedmann and I find her biography perhaps the most fascinating among them all. She was born in 1882 in Hranice na Moravě/Mährisch Weißkirchen. When she was eight, her family moved from her birthplace in Moravia to Vienna (a distance of just about 250 km). Roughly a decade later, she would be a student of physics and maths at the University (after briefly considering to choose languages instead). In 1913, she obtained her doctorate in natural sciences and mathematics. Her education followed two parallel tracks. She worked as a scientist with Lise Meitner, but at the same time also obtained all the necessary qualifications to become a teacher.

The years after the war must have been a difficult but also exciting and forward-looking time for many students, who had an interest in teaching. The monarchy was gone and there was an opportunity to rethink education from scratch. Social scientists, teachers and psychologists set out to find new and more egalitarian teaching methods that would support all students regardless of class or other status. In this environment, Friedmann met Alfred Adler, a medical doctor and psychologist and founder of individual psychology. Adler applied his theories of psychological development to education and educational counseling. Strongly influenced by Adlerian thought, the city of Vienna launched a major schooling reform in 1919/20. Friedmann soon found herself in a professional position to support the project. She became a teacher and then director of a public middle school in Vienna, where she would apply the new methods in practice and lobbied for them among teachers and parents.

The reform was halted after the Austrian civil war of February 1934. The government imposed a new constitution and turned the republic into an anti-liberal and authoritarian corporatist state. Friederike Friedmann lost her job and was retired. After the Anschluss, things deteriorated further. In 1938, an acquaintance of hers denounced her to the Gestapo for her opposition to anti-semitism and the persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi regime. She lost her pension and was sentenced to three months in prison.

In 1939, she could escape to England, where she became a teacher. After the war, she returned to Austria, joined the social democratic party, continued to work for the department of education and became the president of the Association of Individual Psychology. She died in 1968. The first person from the left is Eleonore Albrecht. I could not find much about her CV online. Her research at the time was about branching ratios in the actinum series of the uranium-235 decay chain [E. Albrecht, Sitzungsber. K. Akad. Wiss. Wien, 28, 925–44 (1919)].

Anna Gabler (second one from the left) studied the radioactive decay of radon gas in an electric field. The experimental setup was similar to a Geiger-Müller tube: a metal cylinder with a central clyindrical electrode inside. Gabler measured the accumulation of decay products (so-called active precipitation) at the electrode for different vessels as a function of the voltage applied. At a certain voltage, the accumulation reaches a saturation level. She quantified the saturation and explained her data using Einstein's theory of diffusion [A. Gabler, "Über die Ausbeute an aktivem Niederschlag des Radiums im elektrischen Felde," Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Radiumforschung, Nr. 126, (19??)].

Biographical information about Ludwig Flamm (second row, without a hat) can be easily found online. On his contributions to general relativity, see Gary W. Gibbons, "Editorial note to: Ludwig Flamm, Contributions to Einstein’s theory of gravitation," Gen. Relativ. Gravit., 47, 71 (2015), doi:10.1007/s10714-015-1907-3.

Victor Franz Hess (1883—1963) is the man with the hat in the second row of the picture. After his PhD from the University of Graz, he joined the Institute for Radium Research in Vienna, where he worked from 1910 to 1920 as a research assistant. Upon receiving a professhorship in Graz, he visited the United States for two years, before returning back to Austria working at the Universities of Graz (1923—1931 and 1937—1938) and Innsbruck (1931—1937). He is best know for his discovery of cosmic rays, for which he obtained the Nobel prize in physics in 1936. The small hut that was housing his laboratory in the Karwendel mountain range high above the city of Innsbruck can still be visited today and is easily accesible by cable car from the city centre. An active catholic and supporter of an independent Austrian state, he was dismissed after the Anschluss from his position in Graz. At age 55, he was without a job and had lost his pension plan. His wife was Jewish, he was supportive of the previous government (he had been a member of an advisory body created under the authoritarian 1934 constitution) and the Gestapo threatened to deport him and his wife to a concentration camp. In 1938, the couple escaped the prosecution and moved to the United States. Shortly after his arrival to the U.S., Hess would become a professor at Fordham University in New York. After the war, he was offered a professorship in Innsbruck. The pair decided to stay in the United States. An Austrian pension was never granted.

Grete Richter is the forth woman from the left. She investigated saturation currents generated by the ionizing radiation of Polonium-210 (Radium F in the historical literature).

Maria Szeparowicz is the woman behind Richter. Her research was about the solubility of radon gas (Radium emanantion in the historical literature) in water and benzol as a function of temperature [Maria Szeparowicz, "Untersuchungen über die Verteilung von Radiumemanation in verschiedenen Phasen," Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Radiumforschung, Nr. 128, (19??)].

Hilda Fonovits (1893—1954) is the sixth in the first row from the left. She was born in Vienna, where she did her PhD in physics. During her PhD, she measured the electric current generated by \(\alpha\)-radiation between the plates of a capacitor as a function of the applied voltage for different separation between the plates. The family of plots from her PhD (in the voltage-current plane) made it possible to infer the saturation current, which is a measure of the energy flux of radiation entering the capacitor, from a single measurement of voltage and electric current [Hilda Fonovits, "Über die Erreichung des Sättigungsstromes für \(\alpha\)-Strahlen im Plattenkondensator," Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Radiumforschung, Nr. 117, (1919)].

After her PhD, she continued her research and she became the first female scientist hired by the institute. Her initial contract started in 1921. She got an extension and could have stayed until at least May 1923. After the birth of her son (1922—1941), she left physics and worked for the next decade in the household of her family. In 1931, her former institute established a centre for radiotherapy at a large clinic in Vienna (Wiener städtisches Krankenhaus Lainz). A year later, Fonovits returned to science and became interim head of the experimental lab (Radiumtechnische Versuchsanstalt) of the centre for radiotherapy (Sonderabteilung für Strahlentherapie). Two years later, her position became permanent. At the clinic, she would also meet her second husband, Emil Maier, who was the chief physician of the centre of radiotherapy. Both Fonovits and her husband would die of cancer, likely caused by prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation.

It is possible that Fonovits became knowingly or unknowingly close to some of the darkest chapters of Austrian history. After the Anschluss, German legislation was succesively introduced into Austria by special executive orders from Berlin. This included a law on eugenics (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses). The law created special courts that would allow the Nazi machinery to forcefully sterilize those it deemed unfit, degenerate and genetically inferior. From 1 January 1940 onwards, this law was also imposed in the former Austria. If chirurgical methods could not be used, the doctors had the authority to use ionizing radiation instead. This required special authorization. According to a list from 1942, Fonovits's husband was among those that had this authorization. Unfortunately, there is a lack of historical documents and it is not known, how many — if any — such operations were made (Prof. Herwig Czech, Medical University of Vienna, private communication, 2022).

Erwin Schrödinger (1887—1961), standing in the first row between Fonovits and Thirring. A new biography by David Clary has been published recently by worldscientific, see doi:10.1142/12661.

Hans Thirring (1888—1976). Best known for the discovery of frame dragging, a general relativistic effect that describes the way a rotating mass distorts spacetime. The effect can be measured by the precession of spinning test particles in the gravitational field [J. Lense and H. Thirring, "Über den Einfluß der Eigenrotation der Zentralkörper auf die Bewegung der Planeten und Monde nach der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie," Physikalische Zeitschrift, 19, 156 (1918)]. After the Anschluss, Thirring was forcefully retired. In 1946, he regained his former position and became again a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Vienna. From 1957 to 1963, he was a member of the upper house (Bundesrat) of the Austrian parliament, where he was a representative for the state of Vienna for the social-democratic party. During this time, he lobbied for the unilateral disarmament of Austria during the cold war (Thirring plan). Austria should be a peaceful state without a military. In case of an armed attack against Austrian territory, it should be the collective responsability of the United Nations to defend the country. He was also a passionate skier and developed a sort-of batsuit. The suit had wings that stretched between arms and feet and created lift while going downhill. The Museum of Military History in Vienna (Heeresgeschichtliches Museum) has an interesting article about his activities outside physics, which also includes copies of letters that he sent to the Soviet prime minister Khrushchev and U.S. president Kennedy, see Erik Gornik, "Österreich als Testobjekt der Möglichkeit friedlicher Koexistenz," HGM · Wissensblog, 4 January 2021, available online: blog.hgm.at.

References and further material

- František Veselovský, Peter Ondruš, Jiří Komínek, "History of the Jáchymov (Joachimsthal) ore district," Journal of the Czech Geological Society, 42, 127 - 132 (1997), available online: www.jgeosci.org/detail/JCGS.742.

- Miloš René, "History of Uranium Mining in Central Europe," in Uranium · Safety, Resources, Separation and Thermodynamic Calculation, Nasser S. Awwad, IntechOpen (2017), doi:10.5772/intechopen.71962.

- Brigitte Bischof, PHYSIKERINNEN · 100 Jahre Frauenstudium an den Physikalischen Instituten der Universität Wien, Eigenverlag, Vienna, Austria (1998), available at: fedora.phaidra.univie.ac.at.

- Maria Rentetzi, Trafficking Materials and Gendered Experimental Practices: Radium Research in Early 20th Century Vienna, Columbia University Press, New York, U.S.A. (2009), available at: www.gutenberg-e.org/rentetzi.

- Maria Rentetzi, "Why Women Scientists Thrived at the Radium Institute in Interwar Vienna," Bits of History (2020), available at: www.iqoqi-vienna.at/blogs/bits-of-history.

- Maria Rentetzi, "Designing (For) a New Scientific Discipline: The Location and Architecture of the Institut Für Radiumforschung in Early Twentieth-Century Vienna," The British Journal for the History of Science, 38, 275–306 (2005), doi:10.1017/S0007087405006989.

- Patrice Fuchs, Zwischen Krieg und Euthanasie: Zwangssterilisationen in Wien 1940–1945, Böhlau Verlag Wien · Köln · Weimar (2009), available at: doi:10.25595/413.

- Alfred Adler Center International (AACI), "Friederike Friedmann," AlfredAdler.at, available at: individualpsychology.wordpress.com/friederike-friedmann.

- Clara Kenner, Der zerrissene Himmel: Emigration und Exil der Wiener Individualpsychologie, Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, Göttingen, Germany (2007).

- Claudia Andrea Spring, "Alfred Adler und die pädagogische Revolution," ORF III — zeit.geschichte-Dokumentation, available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=4m0dRnzvT2Y.

- Herbert Pietschmann, "Hans Thirring, a personal recollection," Bits of History (2020), available at: www.iqoqi-vienna.at/blogs/bits-of-history.

- The short abstract above about Anna Gabler's research is based on Anzeiger · Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien · Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, 57, Nr. 1—27 (1920), page 110, file:Anzeiger.pdf and also on Chemisches Zentralblatt, Band III, Nr. 9 (31. August 1921), page 585, file:Chemisches_Zb_1921III9.pdf.

- The short abstract above about Maria Szeparowicz's research is based on Anzeiger · Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien · Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, 57, Nr. 1—27 (1920), page 111, file:Anzeiger.pdf.

- The short abstract above about Eleonore Albrecht's research is based on Chemisches Zentralblatt, Band III, Nr. 8 (24. August 1921), page 12, file:Chemisches_Zb_1921III8.pdf.

ww

Innsbruck, Vienna

December 2021/January 2022